Architecture’s highest calling lies not in creating static forms but in shaping lived experiences that resonate with our deepest capacities for perception, emotion, and meaning. This perspective shifts focus from buildings as aesthetic objects to spaces as dynamic participants in human existence. It emphasises that we understand our surroundings not through detached intellect alone, but through embodied engagement, where the person actively synthesises space through direct, sensory interaction. Space gains meaning through practical involvement, sensory input, and temporal awareness. This foundation reveals how architecture can transform inert materials into poetic environments that speak to our senses, memories, and identities.

Five Essentials of Immersive Design

1. Multisensory Engagement: Beyond Sight

Prioritising visual aesthetics alone impoverishes spatial experience. Authentic encounters arise from integrating touch, sound, scent, and movement. Perception is a whole-body act: textures, acoustics, and thermal qualities actively shape our understanding. Imagine a spa where you hear the water echoing, feel the contrast of hot steam on cool stone underfoot, and smell the mineral vapor – an experience that dissolves the boundaries between body and environment. As one thinker notes, "Every touching experience of architecture is multi-sensory; qualities of matter, space, and scale are measured equally by the eye, ear, nose, skin, tongue, skeleton, and muscle." This holistic engagement fosters profound presence and belonging.

2. Material Authenticity: Truth, Time, and Texture

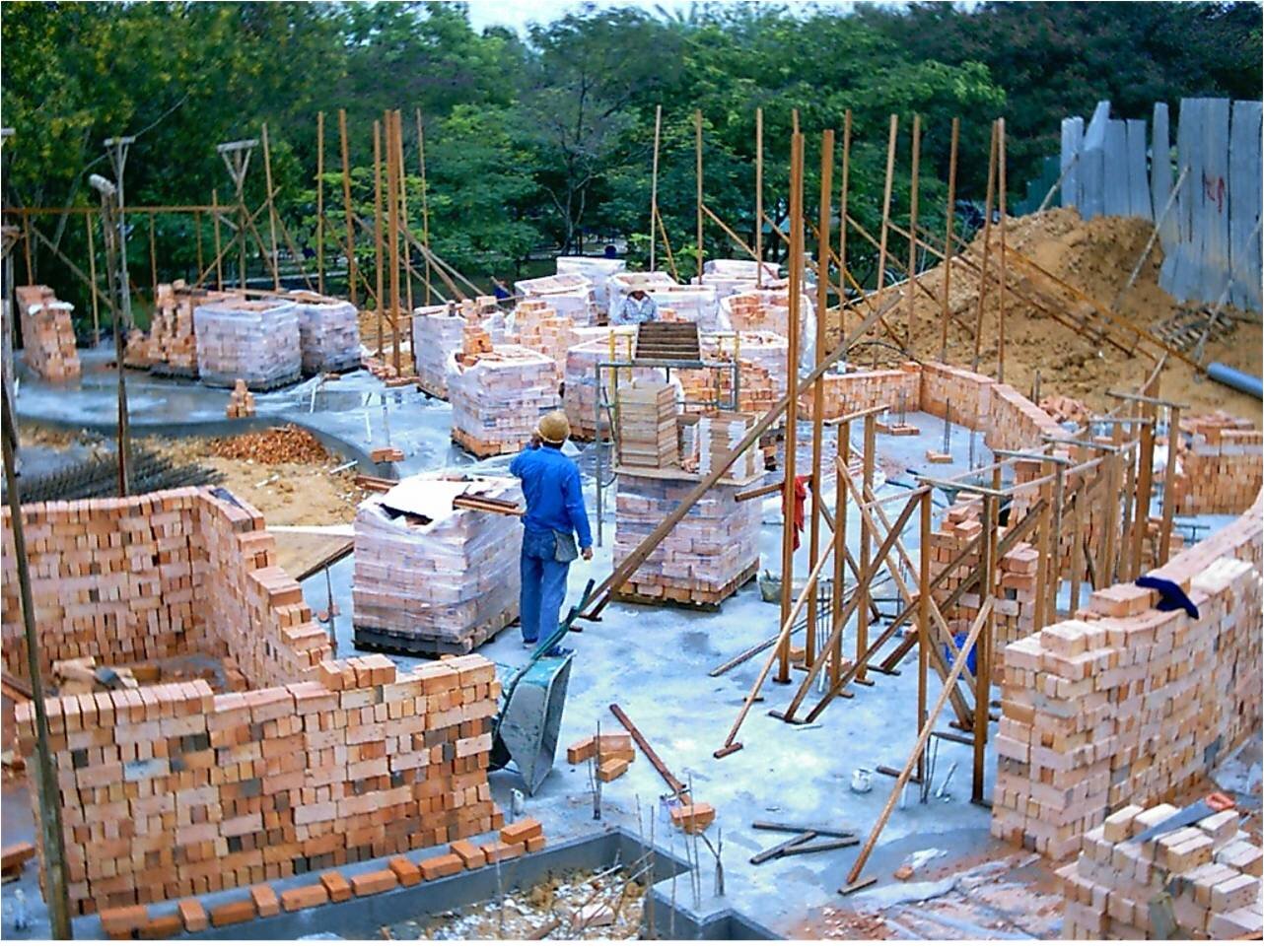

Immersive design demands honesty in materials, not as style, but as an ethical commitment to substance, aging, and place. Materials carry history and cultural memory; their truthful use connects occupants to context and time. Consider brickwork laid without hidden joints, celebrating the raw physicality of clay – its weight, colour variations, and texture defining an atmosphere. Similarly, collaborating with artisans who understand materials like timber on their terms – prioritising inherent strengths and cultural significance over industrial optimisation – roots design in authenticity.

3. Light as Narrative: Shaping Mood and Meaning

Light transcends mere illumination; it becomes a dynamic storyteller, shaping emotional resonance and marking time’s rhythms. Its daily and seasonal transformations make temporality palpable. Deep window reveals can sculpt pockets of shadow, heightening the drama of sunlight. Carefully placed apertures frame views or create ethereal shafts, turning routine activities into ceremonial experiences. Light can paint atmosphere onto the canvas of space, directing focus and evoking introspection through gradients of brightness and shadow.

4. Spirit of Place: Weaving Context

Authentic architecture doesn’t impose but uncovers and nurtures the spirit of a place. This requires deep sensitivity to cultural memory, local traditions, and the physical landscape. A house beside a forest reserve, for instance, might emerge from understanding the inhabitants' lives and a commitment to weave the "forest into the site." The structure fosters ecological connection, achieving a modernity rooted in a specific context rather than abstraction. Integrating sites within their landscapes can evoke contemplation on belonging and life cycles.

5. Temporal Sequences: Spaces as Journeys

Immersive space unfolds over time, choreographing movement to create narrative progression. Architecture becomes a "living language" spoken through thresholds, vistas, and transitions. Designed pathways – with curated views, changing ground levels, and shifts from open vistas to enclosed spaces – structure emotional and spiritual passages. Manipulating compression and release, light and shadow, and material transitions creates rhythmic, almost musical journeys, transforming a visit into a meditative ritual. This unfolding mirrors an experiential adventure for both creator and occupant.

Practical Approaches: Weaving Atmosphere

Translating these principles requires deliberate strategies:

Sensory Layering: Incorporate textured surfaces (rough stone, warm timber), ambient sounds (water, wind), and natural elements to create immersive depth. Attention to the feel of a handrail or the acoustics of a room enriches daily experience.

Cultural Memory as Foundation: Draw from local building traditions, crafts, and historical narratives. Understanding the cultural history of materials prevents architecture from becoming rootless.

Transitional Thresholds: Design meaningful transitions (gateways, courtyards, changing light) and blur indoor-outdoor boundaries to honour movement and connection to nature. Porous boundaries connecting inhabitants to their surroundings exemplify this harmony.

When rooted in this mindful approach, architecture transcends shelter or symbol to become a silent yet eloquent dialogue between occupant and world. Through the authentic weight of materials, the choreography of light, the resonance of sequences, and deep respect for place, architects craft environments felt before they are analysed. Space is not a pre-existing container, but an experience synthesised by the engaged body. This transforms buildings into vessels for human experience, nurturing belonging, introspection, and appreciation for spaces that, like life itself, are constantly evolving encounters. Such architecture consoles, inspires, and ultimately re-enchants our relationship with the built world, proving that the most powerful spaces are not merely seen, but deeply lived.